Date

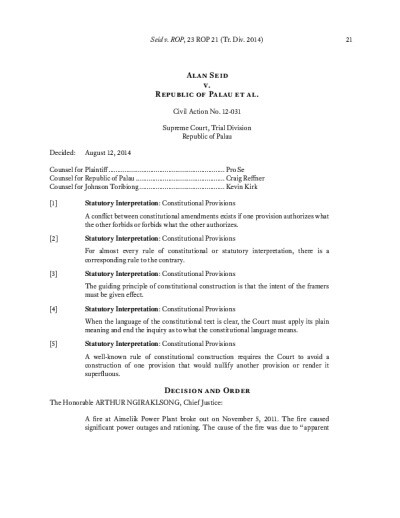

Geographical Area

Pacific

Countries

Palau

Keywords

Case Name

Alan Seid v Republic of Palau et al

Case Reference

Civil Action No. 12-031

Name of Court

Supreme Court, Trial Division

Key Facts

After a fire broke out at the Aimeliik Power Plant on 5 November 2011, causing significant power outages and rationing, the then President of Palau, Johnson Toribiong, declared a state of emergency under Article VIII §14 of the Constitution and assumed legislative powers. The fire was caused by mismanagement and poor maintenance of the power plant.

Seid filed a lawsuit claiming that President Toribiong’s declaration of the state of emergency was not based on any of the enumerated grounds in the Constitution and therefore was unconstitutional.

In 2012, the Court found that the declaration of the state of emergency was unconstitutional, as the Constitution only provides two grounds for the President to invoke the emergency powers: natural catastrophe and human-made grounds (which was limited to war, external aggression or civil rebellion). However, in 2013, the Assistant Attorney-General filed a motion to dismiss, stating that the Palauan word for ‘catastrophe’ (used in the English version of the Constitution), this being ‘kerrior’ (used in the Palauan version), could mean either a natural or human-made disaster. Therefore, as there was a conflict between the two versions, under the 25th amendment to the Constitution, the Palauan version must prevail – concluding that the state of emergency was constitutional. The Court was asked to consider this newly raised issue.

Seid filed a lawsuit claiming that President Toribiong’s declaration of the state of emergency was not based on any of the enumerated grounds in the Constitution and therefore was unconstitutional.

In 2012, the Court found that the declaration of the state of emergency was unconstitutional, as the Constitution only provides two grounds for the President to invoke the emergency powers: natural catastrophe and human-made grounds (which was limited to war, external aggression or civil rebellion). However, in 2013, the Assistant Attorney-General filed a motion to dismiss, stating that the Palauan word for ‘catastrophe’ (used in the English version of the Constitution), this being ‘kerrior’ (used in the Palauan version), could mean either a natural or human-made disaster. Therefore, as there was a conflict between the two versions, under the 25th amendment to the Constitution, the Palauan version must prevail – concluding that the state of emergency was constitutional. The Court was asked to consider this newly raised issue.

Decision and Reasoning

The Court agreed with the argument that ‘kerrior’ could mean a natural or human-made disaster, however, pointed out that so did the word ‘catastrophe’ (using the Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (1961) definition). Therefore, there was no conflict. Instead, the Court noted that the real issue was with the inclusion of the word ‘natural’ before ‘catastrophe’ in the English version and the lack of the Palauan word for ‘natural’ in the Palauan version.

In regards to this issue, the Court stated that there were only two interpretations: that ‘natural’ in the English translation should be read as not existing because there is no Palauan translation in Palauan version; or, ‘natural’ is incorporated in the word ‘kerrior’, so ‘kerrior’ and ‘natural catastrophe’ should be read together to mean any disaster, natural or human-made. The Court rejected both of these interpretations, stating that the only reasonable explanation for the omission in the Palauan version was that ‘natural’ was mistakenly omitted.

Following the guiding principle of constitution construction – that the intent of the framers must be given effect – the Court stated that, as the language of the Constitution’s text is clear (i.e. disasters must be natural or due to war, external aggression or civil rebellion) then the plain meaning should be applied. Furthermore, when there are conflicting sections in the Constitution, constitutional construction states that it should be interpreted so to avoid a construction of one provision that would nullify or render another superfluous. Therefore, to interpret ‘kerrior’ as natural and human-made disasters would render “war, external aggression or civil rebellion” meaningless, so ‘kerrior’ should be construed as meaning only natural catastrophes.

In regards to this issue, the Court stated that there were only two interpretations: that ‘natural’ in the English translation should be read as not existing because there is no Palauan translation in Palauan version; or, ‘natural’ is incorporated in the word ‘kerrior’, so ‘kerrior’ and ‘natural catastrophe’ should be read together to mean any disaster, natural or human-made. The Court rejected both of these interpretations, stating that the only reasonable explanation for the omission in the Palauan version was that ‘natural’ was mistakenly omitted.

Following the guiding principle of constitution construction – that the intent of the framers must be given effect – the Court stated that, as the language of the Constitution’s text is clear (i.e. disasters must be natural or due to war, external aggression or civil rebellion) then the plain meaning should be applied. Furthermore, when there are conflicting sections in the Constitution, constitutional construction states that it should be interpreted so to avoid a construction of one provision that would nullify or render another superfluous. Therefore, to interpret ‘kerrior’ as natural and human-made disasters would render “war, external aggression or civil rebellion” meaningless, so ‘kerrior’ should be construed as meaning only natural catastrophes.

Outcome

The Court denied the motion to dismiss, ruling for the second time that the President’s declaration of a state of emergency was unconstitutional as the catastrophe was not one of the listed types.

Link

Disclaimer

This case law summary was developed as part of the Disaster Law Database (DISLAW) project, and is not an official record of the case.

Document

Document