Date

Geographical Area

Pacific

Countries

New Zealand

Keywords

Case Name

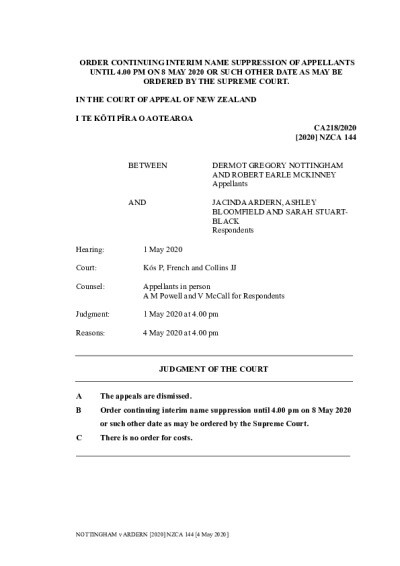

Nottingham & McKinney v Ardern & Ors

Case Reference

[2020] NZCA 144

Name of Court

Court of Appeal of New Zealand

Key Facts

In response to the rising number of Covid-19 cases within New Zealand and internationally, the Government declared a nationwide state of emergency and on 21 May 2020 introduced a four-stage alert system – level 4 being complete lockdown. On 25 March the whole of New Zealand was placed into alert level 4.

As per an order issued on 25 March under s.70(1)(m) of the Health Act 1956, under alert level 4, all premises were to be closed – except private dwellings and essential services – people were banned from congregating, and those permitted to leave their house were to maintain a physical distance of two meters from others. This order was followed, on 3 April, by an order under s.70(1)(f) of the same Act, which required all people to remain in their current place of residence (their ‘bubble’) unless permitted to leave for essential personal movement, and to maintain physical distancing from those except those in their bubble or when accessing/providing an essential service. Both of these orders were revoked on 27 April 2021, when New Zealand moved to alert level 3. Governed by orders under ss.70(1)(f) and (m), alert level 3 permitted people to leave their bubbles for work and education if they had relevant infection control measures in place, relaxed restrictions surrounding exercise and recreation, and permitted people to extend their bubble in certain circumstances.

Nottingham and McKinney, the appellants, alleged that these measures amount to unlawful detention. After their applications for a writ of habeas corpus was dismissed by the High Court in A v Ardern [2020] NZHC 796 and B v Ardern [2020] NZHC 814, they appealed to the Court of Appeal.

As per an order issued on 25 March under s.70(1)(m) of the Health Act 1956, under alert level 4, all premises were to be closed – except private dwellings and essential services – people were banned from congregating, and those permitted to leave their house were to maintain a physical distance of two meters from others. This order was followed, on 3 April, by an order under s.70(1)(f) of the same Act, which required all people to remain in their current place of residence (their ‘bubble’) unless permitted to leave for essential personal movement, and to maintain physical distancing from those except those in their bubble or when accessing/providing an essential service. Both of these orders were revoked on 27 April 2021, when New Zealand moved to alert level 3. Governed by orders under ss.70(1)(f) and (m), alert level 3 permitted people to leave their bubbles for work and education if they had relevant infection control measures in place, relaxed restrictions surrounding exercise and recreation, and permitted people to extend their bubble in certain circumstances.

Nottingham and McKinney, the appellants, alleged that these measures amount to unlawful detention. After their applications for a writ of habeas corpus was dismissed by the High Court in A v Ardern [2020] NZHC 796 and B v Ardern [2020] NZHC 814, they appealed to the Court of Appeal.

Decision and Reasoning

As Nottingham and McKinney sought a writ of habeas corpus, the Court could only consider the circumstances as they existed at the time they heard the appeal – this being level 3.

Considering the definition of detention under the Habeas Corpus Act 2001 – “every form of restraint of liberty of the person” – and noting the primary definition of liberty – to be “free from captivity, imprisonment, slavery, or despotic control” – the Court stressed the importance of not confusing restrictions on a person’s movement (protected by s.18 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990) with restrictions on their liberty. Stating that restrictions on movement vary from imprisonment to mild restrictions, such as requiring passengers to sit during take-off and landing of an aeroplane. For this reason, the Court found that detention must involve more than intermittent or limited constraint upon general movement in order to be considered a restraint on liberty.

Although the Court admitted that level 3 did impose restrictions on movement, they stated that it did permit a wide range of activities including: accessing businesses, services and their jobs given relevant infection control measures were in place, appropriate outdoor exercise or recreation in their region, and extending bubbles to include others. They also mentioned that level 3 did not restrict communications or access to the internet. For these reasons, the Court held that the liberty of Nottingham and McKinney was not restricted by the level 3 order, so they had not been detained.

Considering the definition of detention under the Habeas Corpus Act 2001 – “every form of restraint of liberty of the person” – and noting the primary definition of liberty – to be “free from captivity, imprisonment, slavery, or despotic control” – the Court stressed the importance of not confusing restrictions on a person’s movement (protected by s.18 of the New Zealand Bill of Rights Act 1990) with restrictions on their liberty. Stating that restrictions on movement vary from imprisonment to mild restrictions, such as requiring passengers to sit during take-off and landing of an aeroplane. For this reason, the Court found that detention must involve more than intermittent or limited constraint upon general movement in order to be considered a restraint on liberty.

Although the Court admitted that level 3 did impose restrictions on movement, they stated that it did permit a wide range of activities including: accessing businesses, services and their jobs given relevant infection control measures were in place, appropriate outdoor exercise or recreation in their region, and extending bubbles to include others. They also mentioned that level 3 did not restrict communications or access to the internet. For these reasons, the Court held that the liberty of Nottingham and McKinney was not restricted by the level 3 order, so they had not been detained.

Outcome

The appeal was dismissed. On 17 September 2020, the appellants sought leave to transfer their proceedings to the Court of Appeal under s.59 of the Senior Courts Act 2016 and orders that their proceeding be heard by a full Court. This application was declined: Nottingham v Attorney-General [2020] NZCA 632.

Link

Disclaimer

This case law summary was developed as part of the Disaster Law Database (DISLAW) project, and is not an official record of the case.

Document

Document